Was a Dorset PC dismissed for the actions of a police officer in Minnesota?

The Chair's report into the case of former PC Lorne Castle contains one particular paragraph that should concern anyone who supports confident proactive policing.

Dorset Police finally published the Chair’s report of the misconduct hearing concerning PC Lorne Castle, who was dismissed from Dorset Police without notice following an incident in January 2024.

I’m not going to revisit material I’ve already covered in relation to Dorset Police - and there’s plenty more abour the case to read over at

- but as the panel turned to consider the appropriate sanction there’s a paragraph worth noting.Under a heading of “Harm” - specifically at paragraph 92 - the Chair writes:

"Furthermore, the Panel was mindful of the depth of national concern in relation to the use of unreasonable force by police officers in the course of their duty, particularly given a number of high-profile cases in recent years."

On the surface, this may seem harmless. A recognition of the wider context. An awareness of public trust. But we need to be very careful here.

What it says - not even subtly - is that PC Castle’s case was not judged entirely on its own facts, but against the backdrop of other, unspecified, “high-profile cases” relating to “unreasonable force by police officers in the course of their duty”.

That’s a rather dangerous road to go down.

Misconduct hearings shouldn’t be show trials

The police misconduct regime exists to uphold professional standards, protect the public, and maintain confidence in policing. It rightly expects high standards. But those standards must be applied individually and fairly. Misconduct panels should not be PR tribunals, kangaroo courts or show trials.

Swapping independent Legally Qualified Chairs (LQCs) for senior officers was a move I always opposed - precisely because of the risk that hearings and the outcomes from them end up being weighted more towards what’s best for the reputation of the force or senior officers, than to the justice demanded in the specific circumstances of the case.

The job of these hearings is to weigh the evidence, apply the law, and reach a reasoned and proportionate outcome. What the public thinks about the specific case or force in general - or about other cases they may have read in The Guardian or seen on social media - should not influence decisions about a specific officer’s conduct and the sanction that they face.

The rise of the smartphone and social media mean that the actions of one police officer on the other side of the world can go viral in the UK just moments later. But that doesn’t mean we should allow such viral clips or narratives to interfere with justice in the individual case.

Once we start judging officers or the sanctions they face not on what they, as an individual constable did, but on what others have done, we risk undermining the very idea of a fair trial. That way lies injustice.

Vague references to ‘national concern’ and ‘high profile cases’

As evidenced by much of the reaction to the case of Lorne Castle, including a crowdfunder that has raised more than £128,000 for him and his family, rather undermines any idea that his conduct was of such gravity or likely to so seriously undermine public trust and confidence as to warrant dismissal.

So, what “national concern” and which “high profile cases” are the panel referring to?

Off the top of most people’s heads, there are probably three: the murder of George Floyd, the fatal shooting of Chris Kaba and the manslaughter of Dalian Atkinson.

Could it be that the decision to dismiss PC Lorne Castle was essentially shaped or driven by events that occurred hundreds and even thousands of miles away from Dorset?

It’s not so far-fetched when you consider that the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) were quick to “stand with those appalled by George Floyd death” - nine months before the trials of the police officers involved had even commenced.

It was the first mis-step by police chiefs towards an embrace of American-racial politics, critical race theory and policy that should have little or no sway in the specific and very different UK context.

At the same time, we even saw Chief Constables, Deputy Chief Constables and other senior officers ‘taking the knee’ at BLM-supporting gatherings, like the one below. Pictured are the former Chief Constable of Kent Police with his Deputy Chief Constable and other colleagues in June 2020.

As part of the response to George Floyd, the NPCC and College of Policing announced a controversial and political programme of work: the Police Race Action Plan. Dorset’s current Chief Constable - Amanda Pearson - was, for a period, the Programme Director.

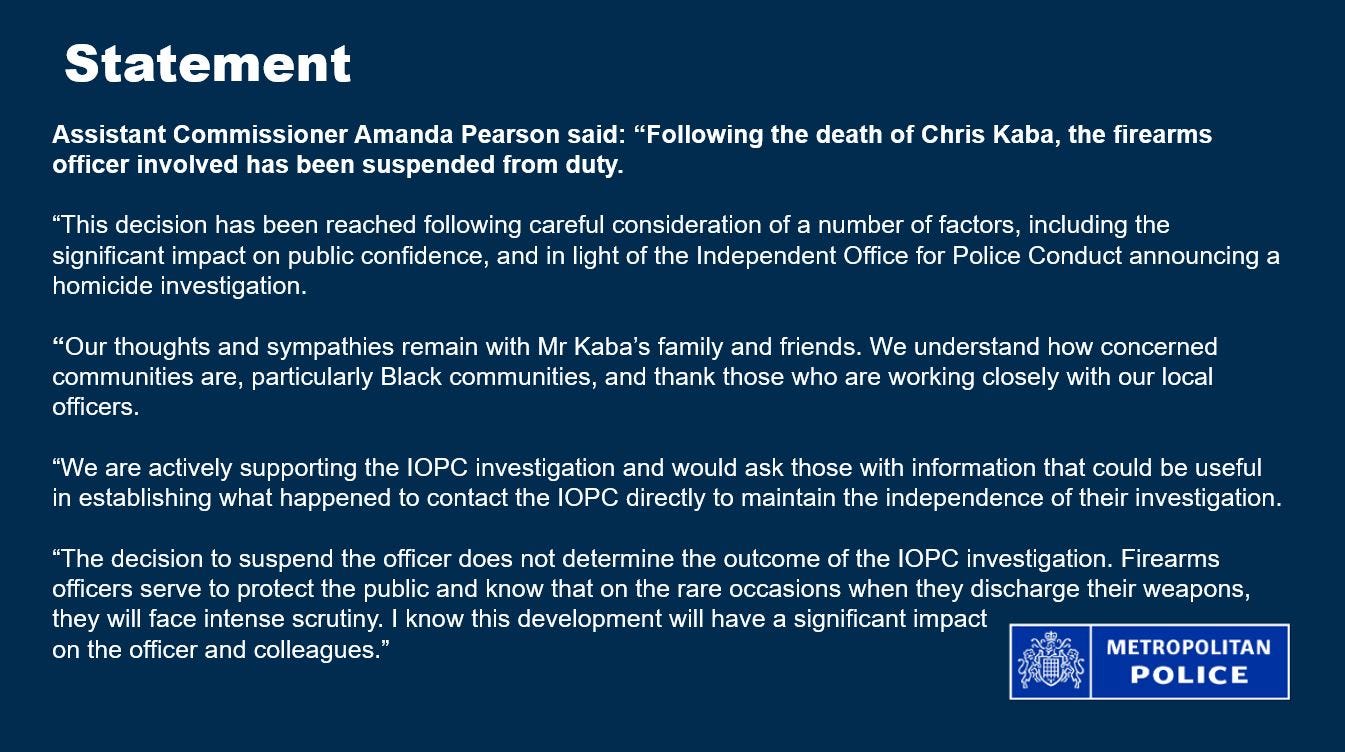

At the time, Pearson had not yet been appointed Chief Constable of Dorset Police. She was a Deputy Assistant Commissioner in the Metropolitan Police, where she can also be connected to the case of Chris Kaba.

A known gangster shot dead by Metropolitan Police officer NX121. NX121 was himself suspended from duty, charged with murder, and swiftly acquitted at trial.

At the time of writing, he still awaits his misconduct hearing.

Pearson made the following statement shortly after the shooting:

The Guardian, at around the same time, reported:

The Met assistant commissioner Amanda Pearson said the force had been trying to allay concerns and anger by talking to community groups

So, at the very least, we know that in recent years, the current Chief Constable of Dorset Police has spent a considerable amount of her time within the orbit of programmes and activity shaped by and doubtless involving discussion of the murder of George Floyd in the United States and the shooting of Chris Kaba.

The manslaughter of Dalian Atkinson, a former professional footballer, will, given his ethnicity, no doubt have also featured in discussions around the Race Action Plan.

Of course, the Chair of the Hearing and the name on the panel’s report is not that of the Chief Constable of Dorset Police, but rather, Assistant Chief Constable Debbie Smith of Wiltshire Police.

As a senior police officer she attended the Strategic Command Course run by the College of Policing in 2020. A forum in which we know that aspiring police chiefs are routinely exposed to and expected to embrace various ideas and speakers of a particular - and generally very selective - political and ideological hue.

While it is undoubtedly true that there has been some national concern about the use of force by police - and rightly so in some cases - it’s also true that much of the concern is amplified and embellished by political activists keen to push agendas.

Much of the public commentary on these issues is ill-informed, emotionally charged, and fuelled by selective clips stripped of context. To allow such concerns - even when well-intentioned - to creep into formal disciplinary findings and outcome decisions is to invite decisions that are reactive, performative, or political, rather than just.

Officers must be held to account. But they are also entitled to be judged independently of the mood of the nation, the mood of vocal activists or the mood of police chiefs with little to lose and something to gain from a ‘heads on sticks’ approach.

If not, misconduct panels will become arenas for reputation management, not justice.

In former PC Lorne Castle’s case, it seems to me that while we might debate over whether he should have ever ended up in a misconduct hearing, what really does seem grossly inappropriate is the sanction: immediate dismissal.

Paragraph 92 sets a precedent - and not a good one

Here’s the nub of it: paragraph 92 takes a step beyond the facts of the case. It introduces external pressures and external events into what should always have been an independent process focussed on the facts of the specific case - and in weighing the harm, the specific harms in this case.

If there are cases of relevance in weighing or assessing the harm in a particular case, then by all means draw upon them, but the Chair should enumerate them clearly - not make vague references to unnamed “high profile cases”.

If this approach becomes standard - perhaps it already is - if perceived public concern and distant or even global events become a routine factor in assessing harm or culpability with a view to the appropriate sanction - then police chiefs are no longer holding a misconduct process. They are holding a weather vane.

That’s not good for fairness or justice. It’s not good for officers. And ultimately, it’s not good for the public or public safety.

Fighting crime and disorder requires confident proactive policing. If police officers fear they won’t be judged fairly on the basis of their actions and the facts of their case (including any harm), then we shouldn’t be surprised when they stop policing as most of us would like: confidently and proactively.

A reasonable and well phrased argument, imho. Perhaps a simpler fact is that the only issue leading to immediate dismissal was swearing. This is disproportionate punishment at best. Experienced officers will know that swearing can easily be justified and in my view PC Lorne was poorly advised in framing his defence. The public have risen to his defence anyway and the reputational damage to the police has shifted from him to his judges. Who will judge them?

Entire discipline system and those who enforce it are immoral hypocrites thinking only of their own position, pensions and prospects. No other career or profession is subject to such zealous fanaticism. None. Especially none that deal with violent, anti social, recidivist criminals, activists and those who just like making lives for police officers as difficult as possible. Police officers can be subject to experiencing 800 traumatic experiences as opposed to an average of 10. No wonder MH is spiralling. No wonder resignations are climbing. No wonder criminals are winning.